One of the most intriguing but often overlooked architectural techniques throughout the rich history of architecture is that of Spolia. Spolia represents the crossroads of heritage, identity, resource reuse, and sustainable architecture.

Spolia is far more than just recycling materials. Spolia architecture represents an innovative perspective on the way we construct, reconstruct, and preserve our architecture in response to the problems that have arisen because of resource challenges and climate change.

What Exactly is Spolia? A Definition Beyond Just Reuse

In Latin, ‘spolia’ is the word used to denote ‘spoils’ or ‘booty.’ This is the kind of thing that was taken during battles or conquests. Stone, columns, reliefs, and decorative architectural elements recycled from another building, most likely from a preceding era, are used to build another building.

This activity is discussed in architectural terms, and it is far more than mere recycling, as the structures are embedded with cultural and economic significance.

Even though the term was first used in architecture during the 16th century, it was used by scholars from the Renaissance who looked down upon the medieval age when referring to the reuse of Roman materials by earlier Romans.

This is a relatively old tradition that appears through different eras, such as Islamic architecture and early Christian basilicas.

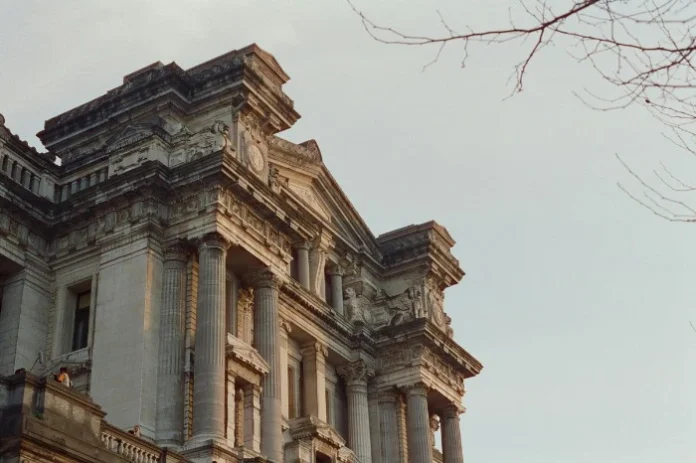

Ancient Practices: From Rome to Cairo

Perhaps the most famous example of spolia are the Arch of Constantine and the Colosseum in Rome. Constructed in the early fourth century CE, the Arch incorporates stones and sculptural reliefs from earlier monuments dedicated to emperors Marcus Aurelius, Hadrian, and Trajan.

More than functional, these spoils provided a visual connection between the rule of Constantine and the accomplishments of his predecessors.

The use of similar customs was widespread in Europe and the Mediterranean. Stones from the Roman Empire, after its decline, were revived in medieval churches. Ancient Egyptian blocks were used to construct the Islamic city walls and structures in Cairo.

It is because of this continuous use of materials, which have been continuously interpreted by different cultures, that spolia architecture has such richness.

A Modern Perspective about Spolia is the Concept of Circular Economy

Though the symbolic aspects of spolia have their antecedents in history, their relevance in the context of the environment is quite up-to-date.

The concept of the circular economy, where the emphasis is on the minimization of waste and seeing demolition as an attribute of new resources rather than an attribute of destruction, is the manner in which architects apply the phenomenon of spolia.

The recycling of materials from demolition sites will considerably decrease carbon emissions associated with transport, manufacturing, and quarrying. In this new view of history, the practice of ancient spolia is no longer a curious practice but a leading case of sustainable architecture.

There are, however, true challenges to its widespread adoption. The construction culture of the present day often favors speed over salvageable materials, especially in the more industrialized regions.

It will take time to methodically dismantle the structures, and often the salvaged materials will not meet the technical specifications mandated within the building codes.

Notwithstanding their importance to the environment and history, materials salvaged can often cost more than materials that are newly produced.

This is being bridged by the emergence of organizations such as Rotor DC in Brussels and Material Index in London. They carefully take apart components, conduct audits of buildings meant for demolition, as well as provide platforms for recycling. They thereby turn architectural salvage into a useful tool for architects.

Spolia in Design Discourse and Education

The academic world has also begun to investigate the application of spolia as a design and research theme. In institutions like the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, courses like Long Living Spolia analyze the role of material longevity, memory, and spolia within the realm of architecture.

In addition to the history of spolia, the courses clearly explore its potential to develop novel approaches to material culture and sustainability within the academic and professional fields of design.

The academic initiative for greater education on spolia clearly identifies the relevance of the concept to the current challenges the world’s cities, heritage sites, and natural systems face.

More Than Just Materials: Stories Embedded in Stones

The rich story that surrounds spolia is what distinguishes it from traditional recycling. A stone that has been recovered from a 2,000-year-old monument has a history that new bricks just cannot match.

It invites people to interact, consciously or unconsciously, with complex layers of narratives about time, power, and culture by placing history in new contexts. When architects use spolia, they are curating historical memories rather than just building structures.

In this way, spolia architecture challenges us to rethink what we value. It pushes us beyond the simple divide of new versus old and raises questions about authenticity, sustainability, and a sense of belonging.

In a time marked by rapid change and ecological urgency, spolia serves as a reminder that the materials we inherit and how we choose to reuse them profoundly shape not only our skylines but our shared memories.